The Butterfield Band performs at Town Hall in New York City on November 26, 1966, following their tour of Great Britain. Daniel Rubin photo

A GALA HOMECOMING concert in New York's Town Hall followed the group's tour of Great Britain. When the Butterfield Band had appeared there a year earlier, they had only been together a few months as a band. Now they were real pros, hardened veterans of the road with a sound that had gone well beyond the music of their native Chicago. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band had become the country's premiere blues-rock group.

But Michael Bloomfield was not happy. A frequent insomniac, he now found that being on the road seriously disrupted his already tenuous ability to sleep. Sleeping pills only exacerbated the condition, and the temptations of the road were a further complication. After a year-and-a-half of constant touring, Michael Bloomfield was reaching the breaking point. On a cold evening in February 1967, he quit the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

While recuperating in New York City and pondering his next move, Bloomfield spent several months playing sessions as a sideman. He recorded with jazz and blues saxophonist Eddie Vinson, folk singer Judy  Barry GoldbergCollins and rock 'n' soul artist Mitch Ryder, among others. It was at the Ryder session, organized by Bloomfield's Chicago friend, Barry Goldberg, that Michael decided he would start his own band – a band with horns. For a long time he and the other members of the Butterfield Band had talked about adding horns to expand their sound, and Michael was particularly inspired by the R&B horn sections that recorded for the Memphis-based Stax label. He had also noticed that American listeners were increasingly infatuated with British bands that played American blues, bands that often didn't play it particularly well. Michael decided that his horn band would play music of all sorts – but that music would be exclusively American music, the way it should be played.

Barry GoldbergCollins and rock 'n' soul artist Mitch Ryder, among others. It was at the Ryder session, organized by Bloomfield's Chicago friend, Barry Goldberg, that Michael decided he would start his own band – a band with horns. For a long time he and the other members of the Butterfield Band had talked about adding horns to expand their sound, and Michael was particularly inspired by the R&B horn sections that recorded for the Memphis-based Stax label. He had also noticed that American listeners were increasingly infatuated with British bands that played American blues, bands that often didn't play it particularly well. Michael decided that his horn band would play music of all sorts – but that music would be exclusively American music, the way it should be played.

Michael asked Barry Goldberg if he'd help form the band. Goldberg readily agreed. The two first enlisted Harvey Brooks, a bassist Michael had met at the Dylan "Highway 61" sessions. Brooks suggested a drummer he knew of who was working with Wilson Pickett, a huge teenager from Omaha named George "Buddy" Miles. Nick Gravenites, who had left Chicago and was living in San Francisco, was selected to be the band's singer. For the horn section, Barry recruited a saxophonist he had worked with in Chicago, a New Haven native named Peter Strazza. Guitarist Larry Coryell recommended a trumpeter with exceptional tone that he knew from Seattle named Marcus Doubleday. Doubleday had worked with the Drifters, Jan and Dean, and Bobby Vinton.

The Electric Flag, an American Music Band, right after its formation in the summer of 1967. From left, Nick Gravenites, Barry Goldberg, Marcus Doubleday, Harvey Brooks, Peter Strazza, Michael Bloomfield and Buddy Miles (and friend). Photo taken for ABGM promotional material

The Electric Flag, an American Music Band, right after its formation in the summer of 1967. From left, Nick Gravenites, Barry Goldberg, Marcus Doubleday, Harvey Brooks, Peter Strazza, Michael Bloomfield and Buddy Miles (and friend). Photo taken for ABGM promotional material

Albert Grossman agreed to manage the new group, and Bloomfield decided to base it in San Francisco, a town that in 1967 was at the epicenter of American pop culture. By April he had rented a house in Mill Valley and was beginning to work on material with the group. But before he could even decide on a name for the band, actor Peter Fonda came calling. Fonda, Jack Nicholson and filmmaker Roger Corman were working on a feature film about LSD called "The Trip" and they wanted a cutting-edge band to create its soundtrack. Fonda knew of Bloomfield from his days with Butterfield, and in short order he arranged with Grossman for Bloomfield and company to travel to Los Angeles to record music for the film.

Bloomfield experimented both in the studio and out in capturing sonically the nature of the experience that Corman wanted to bring to the big screen. Under Michael's guidance, the band created music in a variety of styles that ranged from sound pieces and free jazz to pop ditties and hard blues. In all, they spent a week-and-a-half in the studio. Bloomfield remained in L.A. to edit the material to the on-screen action for an additional few weeks.

Roger CormanRoger Corman was exceedingly pleased with the music and used it in nearly every scene of "The Trip." Plans were made for a Capitol subsidiary, Sidewalk Records, to release the soundtrack concurrent with the opening of the movie in the fall.

Roger CormanRoger Corman was exceedingly pleased with the music and used it in nearly every scene of "The Trip." Plans were made for a Capitol subsidiary, Sidewalk Records, to release the soundtrack concurrent with the opening of the movie in the fall.

While Bloomfield was finishing up the soundtrack, Grossman sent word that the band would be making its debut in June – at the Monterey Pop Festival. Originally proposed as an event to validate rock music as an art form, much as the Monterey Jazz festival had done for jazz, the Monterey Pop Festival had grown into a major industry showcase for dozens of underground American and British acts. Grossman informed Michael that representatives from the Columbia and Atlantic record labels would be on hand to see the new group perform. If they liked what they heard, Albert said, it was quite likely that the band would receive a very generous contract from the winning bidder.

The pressure on the band was enormous.

BLOOMFIELD HAD ONLY a few weeks to rehearse the group and get its sound together. While they had begun work on several original tunes before focusing on "The Trip," they really had no repertoire to speak of. In addition, the band had no real name. A friend of Nick Gravenites had a novelty American flag with a small fan in its base that caused the flag to flap in the breeze. Michael thought it was hilarious, and persuaded the friend to give it to the band. The new group suddenly had a name: the Electric Flag.

Monterey was organized as a three-day cultural extravaganza with Saturday afternoon reserved for the blues. It was to feature a line-up of eight bands, with Bloomfield and company scheduled to close the show. It was a prime slot for a band that was highly anticipated by audience members and fellow musicians alike. Michael soon realized that the band's performance would be more than just the auspicious debut of a new, horn-infused rock band. It would be the measure of himself as a musician and as an American icon.

Mike Bloomfield and Harvey Brooks conclude "Groovin' Is Easy," the Electric Flag's opening number at the Monterey International Pop Festival on June 17, 1967. Screen grab from "Monterey Pop"Saturday afternoon the show got underway with the Los Angeles band Canned Heat, and progressed through performances by Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield and several other groups. The Flag's set was short – they'd only prepared four tunes – but it was driven by an exciting, barely-contained manic energy. Buddy Miles sang two ebullient numbers while Nick Gravenites did the band's signature tune, "Groovin' Is Easy," and the closer, "Wine." Michael soloed like a man possessed and turned in a thrilling performance on "Wine." The audience stood and cheered, demanding an encore, and the band reluctantly complied. The Electric Flag had not disappointed.

Mike Bloomfield and Harvey Brooks conclude "Groovin' Is Easy," the Electric Flag's opening number at the Monterey International Pop Festival on June 17, 1967. Screen grab from "Monterey Pop"Saturday afternoon the show got underway with the Los Angeles band Canned Heat, and progressed through performances by Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield and several other groups. The Flag's set was short – they'd only prepared four tunes – but it was driven by an exciting, barely-contained manic energy. Buddy Miles sang two ebullient numbers while Nick Gravenites did the band's signature tune, "Groovin' Is Easy," and the closer, "Wine." Michael soloed like a man possessed and turned in a thrilling performance on "Wine." The audience stood and cheered, demanding an encore, and the band reluctantly complied. The Electric Flag had not disappointed.

But Michael Bloomfield was shaken. He later said he thought the band played badly, well below the standard they set for themselves. He said that even though their performance was off, the audience loved them anyway. "Festival madness," he called it. For the first time, he said, he realized that much of what the music industry was about had little or nothing to do with music. Hyping a commodity, selling an image, marketing a product – the music business was about business. And Bloomfield did not want to be a part of that.

It was a turning point for Michael. But there was another reason he was distressed.

When Jimi Hendrix took the stage on Sunday evening, he was largely unknown in America. Forty-five  Jimi Hendrix, playing guitar behind his back, gives a career-making performance at Monterey in June 1968.minutes later, he had created a sensation and the pop world would never be the same. Whatever the audience may have thought of his onstage antics, the Seattle guitarist was clearly a extraordinary player. And his approach brought something entirely new to pop music.

Jimi Hendrix, playing guitar behind his back, gives a career-making performance at Monterey in June 1968.minutes later, he had created a sensation and the pop world would never be the same. Whatever the audience may have thought of his onstage antics, the Seattle guitarist was clearly a extraordinary player. And his approach brought something entirely new to pop music.

Seeing Hendrix's set, Bloomfield – the greatest American blues-rock guitarist – must have realized that he was seeing the future. A future that he, Michael Bloomfield, could not be a part of. He had known that Hendrix was great, but now for the first time he saw that Jimi's abilities as a performer were as electrifying as his guitar playing. Hendrix was doing things that Michael couldn't do, for Bloomfield was a player – and an extraordinary one – but by his own admission he was not a entertainer. That evening Michael Bloomfield must have felt like one of the old folkies at Newport when Dylan walked onstage with an electric guitar.

IT WAS WITH COLUMBIA'S Clive Davis that Albert Grossman successfully negotiated a deal following the Flag's Monterey appearance. The band would record for the label that had successfully marketed Grossman's star client, Bob Dylan. Michael and the group were surprised by the choice – they thought their music was better suited for Jerry Wexler and the Atlantic label. After all, much of the music they admired have been released on Atlantic. But Grossman was able to get more money from Columbia, and that sealed the deal.

The Heliport in Sausalito. Photo by Kim RushThe Flag rented rehearsal space at Sausalito's Heliport, an old helicopter hanger used by local bands as a place to practice, and began working up material. In September, the band was booked for several weeks into the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, the venue Michael had played numerous times as a member of the Butterfield Blues Band. On the evening of September 30, police officers responding to a noise complaint arrested Barry Goldberg, Harvey Brooks, Nick Gravenites and Bloomfield in Goldberg's room at the Huntington Beach Motel. The four had been caught with marijuana, a "narcotics violation." They were arraigned at the police station and given a court date of October 20.

The Heliport in Sausalito. Photo by Kim RushThe Flag rented rehearsal space at Sausalito's Heliport, an old helicopter hanger used by local bands as a place to practice, and began working up material. In September, the band was booked for several weeks into the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, the venue Michael had played numerous times as a member of the Butterfield Blues Band. On the evening of September 30, police officers responding to a noise complaint arrested Barry Goldberg, Harvey Brooks, Nick Gravenites and Bloomfield in Goldberg's room at the Huntington Beach Motel. The four had been caught with marijuana, a "narcotics violation." They were arraigned at the police station and given a court date of October 20.

While no small matter, the Flag's Huntington Beach bust was only a symptom of a much larger problem – that of hard drug use among certain members of the band. While grass and LSD were commonly used by most of the members, Marcus Doubleday had been a habitual heroin user before joining the band and Peter Strazza was soon addicted. Barry had started using the drug before leaving New York, and Michael, who at first was unaware of the horn players' narcotics use, was soon experimenting with heroin, too. A roadie with the band acted as procurer, and in short order the Flag was often flying on more than just its musical prowess.

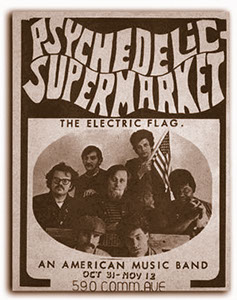

The court appearance delayed the band's first real road trip until the third week in October. Beginning  October 23, the Flag spent a month on the road, traveling to Wisconsin and Massachusetts before appearing in New York City for their official East Coast debut. To get their sets together, they did several weeks at a converted parking garage in Boston called the Psychedelic Supermarket. Reviews were good, even though the Flag had only its single, "Groovin' Is Easy," for support. The band featured a mix of soul covers, blues and a handful of originals, all leavened with Michael's protean solos and Buddy Miles' overwrought vocals.

October 23, the Flag spent a month on the road, traveling to Wisconsin and Massachusetts before appearing in New York City for their official East Coast debut. To get their sets together, they did several weeks at a converted parking garage in Boston called the Psychedelic Supermarket. Reviews were good, even though the Flag had only its single, "Groovin' Is Easy," for support. The band featured a mix of soul covers, blues and a handful of originals, all leavened with Michael's protean solos and Buddy Miles' overwrought vocals.

The shows were tight, impressive and hugely entertaining. But they were also considerably more conventional than the band's earlier work for "The Trip." The experimentation that marked Bloomfield's material for Roger Corman seemed to have gotten lost in the need to rapidly assemble a book of tunes for the Flag's many performance dates. Bloomfield's vision of music drawn from across the spectrum of American styles seemed to have been abandoned in favor of a jumble of standard blues and R&B numbers.

There were exceptions. "Another Country," by Nick Gravenites, featured a startling free-form section, a sound collage that morphed into a jazzy guitar-and-rhythm solo from Michael. And there were occasional extended jams that evoked the "East-West" days and allowed Bloomfield to explore the outer reaches of his formidable talent.

In New York City, the band played two weeks at the Bitter End. The New York Times touted their arrival, but the Flag's appearance was complicated by the loss of one of its founding members.

Buddy Miles works the crowd as Michael Bloomfield accompanies him during the Electric Flag's New York debut at the Bitter End in November 1967. Don Paulsen photo for Hit ParaderBarry Goldberg, fearful of becoming a full-blown junkie and increasingly reluctant to travel, decided to leave the band soon after the Boston gig ended. He was quickly replaced by a fine player from Canada, a friend of Buddy Miles' named Michael Fonfara. The band's sound was not significantly affected, but the departure of Bloomfield's long-time friend further shifted the balance of control toward Buddy Miles and also underscored the real threat that drugs posed.

Buddy Miles works the crowd as Michael Bloomfield accompanies him during the Electric Flag's New York debut at the Bitter End in November 1967. Don Paulsen photo for Hit ParaderBarry Goldberg, fearful of becoming a full-blown junkie and increasingly reluctant to travel, decided to leave the band soon after the Boston gig ended. He was quickly replaced by a fine player from Canada, a friend of Buddy Miles' named Michael Fonfara. The band's sound was not significantly affected, but the departure of Bloomfield's long-time friend further shifted the balance of control toward Buddy Miles and also underscored the real threat that drugs posed.

Despite the changes, though, the Flag had a triumphant homecoming weekend at the Fillmore and Winterland for Bill Graham. Though the Byrds were headlining, B.B. King was also on the bill and Michael – having arranged for the Flag to go on first – took great pleasure in introducing his idol to the uninitiated in the audience.

BUT THINGS WERE not well in the Bloomfield household. Susan, Michael's wife of five years, announced in December that she had decided to leave him. With Michael preoccupied with the welfare of his band, out at gigs or on the road much of the time and at home primarily to catch up on his sleep, she felt they had grown apart. She and Michael separated in early 1967.

There were more personnel changes in the band, too. Mike Fonfara had been arrested for drug possession in Los Angeles in mid-December and – because he was not an American citizen – had been dropped from the band on Grossman's orders. Baritone player Herbie Rich, a talented multi-instrumentalist, took over keyboard duties. Buddy added another friend form Omaha to fill out the horn section, a saxophonist named Stemzie Hunter

Gigs at the Fillmore, the Avalon and other California venues filled out the months of January and February. At the end of February, Rolling Stone magazine editor  Jann WennerJann Wenner did an extensive interview with Michael. The two discussed Michael's early days in Chicago, his stints with Dylan and Butterfield, and his thoughts about the Electric Flag. Wenner also got Bloomfield to speak on a range of other topics, including the role of race in music, the San Francisco scene and the blues. The interview was scheduled to appear in April, right around the time Columbia hoped to have the Flag's first record in store bins.

Jann WennerJann Wenner did an extensive interview with Michael. The two discussed Michael's early days in Chicago, his stints with Dylan and Butterfield, and his thoughts about the Electric Flag. Wenner also got Bloomfield to speak on a range of other topics, including the role of race in music, the San Francisco scene and the blues. The interview was scheduled to appear in April, right around the time Columbia hoped to have the Flag's first record in store bins.

The band was soon back on the road, heading to New York City for a show at the Anderson Theater and a two-week stand at the Cafe Au Go Go. Then, on March 19, the Flag again ran afoul of its bad habits. While enroute to the West Coast, they played a show in Detroit and were robbed in their motel rooms. The event was reported as a brazen hold-up, but it was almost certainly a drug deal gone bad. A member of the band had been short of cash while making a buy, and the enraged dealers took him at gun point into the other members' rooms in search of their money. They made off with whatever they could find, and Grossman had to wire the band additional funds to complete the trip home.

By the spring of 1968, drug use in the Flag had become a serious problem. In addition to putting the band at risk, it was also affecting the Electric Flag's ability to perform. There were other complications for Michael, too. Buddy Miles, a force to be reckoned with from the start, had effectively taken over the band by April 1968. His stage routine was built around the Chitlin' Circuit antics he had learned with Wilson Pickett and other soul shouters, and he loved nothing more than to whip the audience into a frenzy with vocal feints and histrionics, false endings, "clap-your-hands" interludes and impromptu call-and-response moments. He would leave the drums in mid-performance and cavort around the stage, mic in hand, improvising lyrics and generally taking over. While audiences were usually thrilled by Buddy's showboating, Michael hated it. "I'm no entertainer," he later said. His experience at Monterey was no doubt still fresh in his mind.

"A Long Time Comin'," the Electric Flag's long-await debut release, finally reached record store bins the  first week in April. The hype surrounding the band at Monterey had long since dissipated, and while the record was quite good by contemporary standards, it received mixed reviews and had little impact on the pop music world. It rose briefly to number 31 on Billboard's charts, a fair showing, but well short of the success originally expected for Michael Bloomfield's American music band.

first week in April. The hype surrounding the band at Monterey had long since dissipated, and while the record was quite good by contemporary standards, it received mixed reviews and had little impact on the pop music world. It rose briefly to number 31 on Billboard's charts, a fair showing, but well short of the success originally expected for Michael Bloomfield's American music band.

Concurrently, Rolling Stone's interview with Mike Bloomfield appeared in the April 6 issue. Bloomfield's ideas on music, race, blues, rock 'n' roll and his own place in their evolution were spread across five full pages, with the promise of a second installment in the magazine's subsequent issue. Michael came off as a highly animated, a larger-than-life savant whose opinions were hard-edged and legion. His respect for his antecedents and his disdain for musical wannabes – especially those found in San Francisco – was offered with unqualified and assured candor. It was the world according to Michael Bloomfield.

Oddly, there were no plans for the Electric Flag to tour in support of their Columbia release. They continued to play venues in San Francisco and Los Angeles, but there were no preparations for a third cross-country junket to promote "A Long Time Comin'." Bloomfield, who by May 1968 was thoroughly disillusioned with the group, may have told Grossman that he wouldn't go along on another road trip. In fact, he told Albert that he intended to quit the band he had formed nearly one year ago.

ON MAY 11, BLOOMFIELD was caught off guard by a column in Rolling Stone. San Francisco jazz critic and icon, Ralph Gleason, lambasted Michael for things he said in his interview and for his failure – in Gleason's  Ralph Gleasonopinion – to find his own voice with the Flag. Headlined "Stop this shuck, Mike Bloomfield," the caustic column punctured Michael's apparent inflated sense of himself and came off as an ad homonym bromide that questioned the guitarist's ability to play blues based on his racial background. Gleason's main criticism, though, was a valid one, and must have hit home. He chided Bloomfield for not fulfilling his potential as "one of the best guitar players in the world."

Ralph Gleasonopinion – to find his own voice with the Flag. Headlined "Stop this shuck, Mike Bloomfield," the caustic column punctured Michael's apparent inflated sense of himself and came off as an ad homonym bromide that questioned the guitarist's ability to play blues based on his racial background. Gleason's main criticism, though, was a valid one, and must have hit home. He chided Bloomfield for not fulfilling his potential as "one of the best guitar players in the world."

The discomfort of Monterey's failure had been captured in a single sentence.

Michael's friend and fellow bandmate, Nick Gravenites, wrote a bristling response to Gleason in the next edition of Rolling Stone. He vigorously defended Bloomfield's right to play a music he had grown up with, but the damage was done. Michael was thoroughly disheartened by Gleason's accusations, and he was more determined than ever to remove himself from the spotlight.

But while Bloomfield was trying to extricate himself from the Electric Flag, he got a call from Al Kooper. Kooper, who had recently quit his own horn band Blood, Sweat & Tears, was working as an A&R man for Columbia. He needed a project, and he proposed to Michael that they go into the studio, jam on a few tunes and see what would happen. It would be a session not unlike what jazz artists had been doing for decades. Michael reluctantly agreed to the plan and met Kooper in a Los Angeles studio on the evening of May 28. They were joined by Eddie Hoh, the drummer from The Mamas & the Papas, and the Flag's bass player, Harvey Brooks. Barry Goldberg sat in on piano. Over the course of six hours, they recorded five impressive tunes and then retired for the night.

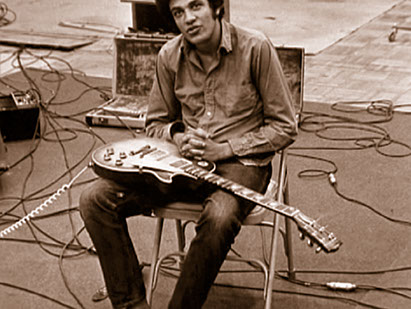

Bloomfield takes a break during Al Kooper's May 28, 1968 jam session date in Los Angeles, a taping that resulted in "Super Session." Jim Marshall photoIn the morning, Bloomfield was nowhere to be seen. He later told Kooper that he couldn't sleep and had decided to go home to Mill Valley. Kooper suspected that his departure was drug related. In any event, Al enlisted Steve Stills to complete the session.

Bloomfield takes a break during Al Kooper's May 28, 1968 jam session date in Los Angeles, a taping that resulted in "Super Session." Jim Marshall photoIn the morning, Bloomfield was nowhere to be seen. He later told Kooper that he couldn't sleep and had decided to go home to Mill Valley. Kooper suspected that his departure was drug related. In any event, Al enlisted Steve Stills to complete the session.

Michael made arrangements to reimburse Albert Grossman for advances and other expenses related to the Electric Flag and was officially through with the band by June following an appearance with the Flag at Graham's newly-opened Fillmore East. The Electric Flag played its last shows with Michael Bloomfield on June 7 and 8 in New York City. The New York Times called their final appearance a "sentimental moment and a crossroads event."

And then the original Electric Flag was no more.

Mike Bloomfield retired to his home on Wellesley Court in Mill Valley, just as he had done after leaving the Butterfield Band. But this time he was not energized, ready to strike out on his own. He visited his family in Chicago, recorded as a sideman for Barry Goldberg and for a new group produced by Mark Naftalin called Mother Earth, and tried to sort things out.

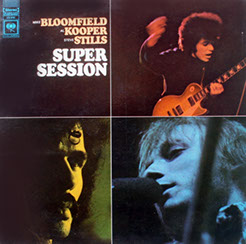

The album that he had recorded with Al Kooper in May was released in August. Called "Super Session," Bloomfield was featured on one side and Steve Stills on the other. It was a surprise hit, reaching number 12  on Billboard's charts. Critics agreed that Bloomfield's playing was masterful, and Kooper prided himself on having captured for the first time in the studio the guitarist's distinctive sound. Michael, who initially thought he had played well, was appalled by the superficiality of the result. He felt that the elevation of a casual jam to "super" status was nothing more than music business cynicism. Privately, though, he could not have missed the irony in the fact that "A Long Time Comin'," an album he had spent months laboring to create while battling with Columbia's conservative engineers and attempting to expand upon the innovations of producers like Bob Crewe and Phil Spector, had received a tepid response upon release, while an impromptu jam session that nearly hadn't happened was receiving accolades.

on Billboard's charts. Critics agreed that Bloomfield's playing was masterful, and Kooper prided himself on having captured for the first time in the studio the guitarist's distinctive sound. Michael, who initially thought he had played well, was appalled by the superficiality of the result. He felt that the elevation of a casual jam to "super" status was nothing more than music business cynicism. Privately, though, he could not have missed the irony in the fact that "A Long Time Comin'," an album he had spent months laboring to create while battling with Columbia's conservative engineers and attempting to expand upon the innovations of producers like Bob Crewe and Phil Spector, had received a tepid response upon release, while an impromptu jam session that nearly hadn't happened was receiving accolades.

BLOOMFIELD CHRONOLOGY continued

CONTACT | ©2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD | AN AMERICAN GUITARIST