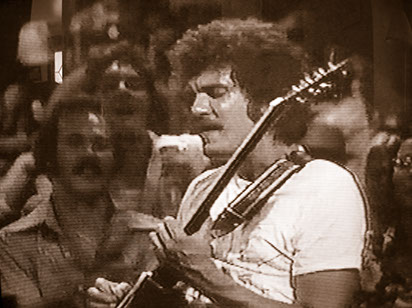

Michael Bloomfield and Friends at the Bottom Line in New York on January 26, 1975, with guest Paul Butterfield. From left, Mark Naftalin, Bloomfield, George Rains, Butterfield and Jellyroll Troy. Chuck Pulin photo

Michael began work on his second Columbia album in 1974, composing a slew of new tunes, including six of that would eventually be selected for the record. One, called "Midnight on the Radio," happily recalled Michael's early days listening to blues on his transistor radio. Another – "When It All Comes Down" – recounted a troubled relationship, but did so from a place of strength and resolve. Gone were the intensely personal and pained confessions of his first Columbia solo effort. The album was to have a healthy mix of pop, rock, blues, soul and gospel selections, and would have likely been a commercial success.

But despite the effort Michael put into the July sessions, Columbia was hesitant to take a chance on another Bloomfield production and decided against going ahead with the release. "Try It Before You Buy It," as the album was to be titled, was shelved.

Also in 1974, the IRS informed the guitarist that he owed a substantial amount in unpaid taxes and penalties from 1968-1972. In those chaotic years when Bloomfield had been between bands and managers, the guitarist had let the business end of things slide. And now he had to come up with a substantial amount of cash to make good on the debt. If Michael needed a compelling reason to continue to perform and tour, he now had one.

It was then that a friend called with a proposal. Barry Goldberg wanted to get the Electric Flag back together. He had sold Atlantic Records in the concept, and had gotten Nick Gravenites and Buddy Miles on board. Legendary producer Jerry Wexler was going to oversee the creation of a reunion LP, and the sessions would be at Wexler's favorite studio in Miami with Tom Dowd as engineer. There was the potential to make lots of money. Was Michael interested?

He was.

In June, the former Flag members flew to Florida and for several weeks struggled to capture the old fire. Buddy, who had gone on to work with Jimi Hendrix after leaving the Flag and had headed his own band called the Buddy Miles Express,  Producer Jerry Wexler works with Mike Bloomfield during recording sessions in Miami in 1974. Unknown photographerhad become accustomed to doing things his own way and wanted to play guitar rather than drums. When conflicts arose between the players, Nick tired to act as mediator, defusing spats and smoothing egos, but the sessions were contentious. Despite the strife, though, the Flag's reunited players were able to complete some twenty tunes.

Producer Jerry Wexler works with Mike Bloomfield during recording sessions in Miami in 1974. Unknown photographerhad become accustomed to doing things his own way and wanted to play guitar rather than drums. When conflicts arose between the players, Nick tired to act as mediator, defusing spats and smoothing egos, but the sessions were contentious. Despite the strife, though, the Flag's reunited players were able to complete some twenty tunes.

Michael returned to Mill Valley after the sessions, thoroughly disgusted with the project. He had gotten involved primarily to make money and once again his low opinion of commercial entities known as "super groups" was confirmed. It had been yet another "scam" as far as he was concerned. But the need for income remained and when the opportunity arose for the reconstituted Electric Flag to tour, Bloomfield reluctantly went along.

But first he had a date to play in Chicago.

WTTW-TV was producing a tribute to Muddy Waters that would feature many of Muddy's contemporaries as well as some of the young players who had learned their craft from the great Chicago bluesman. Called "Blues Summit in Chicago," the hour-long special would include Muddy and his working band with Chicago mainstays Willie Dixon, Junior Wells and Koko Taylor. Joining the party would be Dr. John, Buddy Miles, Johnny Winter and Nick Gravenites.

In the TV studio, Bloomfield acted as Muddy's music director. His soloing was subdued, partially out of deference to the great bluesman, but Muddy appeared to thoroughly enjoy himself. At the end of the hour, Michael rushed across the stage and gave the man he once called his "other father" a huge bear hug. Bloomfield solos during PBS's "Soundstage" tribute to Muddy Waters. From WTTW-TV broadcast

Bloomfield solos during PBS's "Soundstage" tribute to Muddy Waters. From WTTW-TV broadcast

Following his "Blues Summit" appearance, Bloomfield joined the members of the Electric Flag in Sedalia, MO, for the reformed band's debut performance. They did a set under the blazing sun at the Ozark Music Festival, a weekend counterculture extravaganza that featured dozens of name rock bands and rivaled Woodstock for the size of the crowd it attracted. Unlike Woodstock, though, the Sedalia festival descended into a drug–fueled mêlée that resulted in serious injuries and extensive property damage. The Flag escaped unscathed and even garnered a positive review in a local paper.

Other performances followed. The band played a number of venues in California, and then headed east for a weekend at New York City's Bottom Line. On the way they did shows in Illinois, Pennsylvania and on Long Island and Cape Cod. In November, their Atlantic release – optimistically titled "The Band Played On" – was released. But by that time, however, the principal members had lost interest in the band, and the Flag was rumored to be on the verge of splitting up. Michael joked to the press that he was thinking of quitting and opening up a "chain of massage parlors for women."

The Flag hung on for two more shows in January 1975, probably because the venues were in exotic Hawaii. But after that, the group once again broke up. Michael returned to gigging in the San Francisco area with & Friends.

IN EARLY 1975, word got around that Mike Bloomfield, former rock star and guitar legend, had sunk so low that he was forced to make music for pornographic movies.

The truth was that Bloomfield had been introduced to the Mitchell brothers, two adult film entrepreneurs who wanted to put an artistic gloss on their product by hiring legitimate composers. Michael, always in need of money due to his ongoing tax difficulties, agreed to  A still from a scene in "Hot Nazis," one of the Mitchell brothers films that Michael Bloomfield created a soundtrack for in 1975.create soundtracks for them at a rate $1,000 per hour of music. He said later that he rarely ever saw the actual scenes he scored but worked instead from scripts and timing sheets. By the end of the year had produced soundtracks for half a dozen of the Mitchell's films. Though he treated the work as just another gig and strove to make the best music he could, there no doubt was a part of him that secretly enjoyed tweaking the nose of the critical establishment.

A still from a scene in "Hot Nazis," one of the Mitchell brothers films that Michael Bloomfield created a soundtrack for in 1975.create soundtracks for them at a rate $1,000 per hour of music. He said later that he rarely ever saw the actual scenes he scored but worked instead from scripts and timing sheets. By the end of the year had produced soundtracks for half a dozen of the Mitchell's films. Though he treated the work as just another gig and strove to make the best music he could, there no doubt was a part of him that secretly enjoyed tweaking the nose of the critical establishment.

In January, Michael returned to the Bottom Line where he and an & Friends ensemble that included Barry Goldberg and guest flutist Jeremy Steig played to sold out houses. Fans were also treated to a reunion of sorts when Paul Butterfield sat in on one of the nights.

A session for Charlie Musselwhite and Capitol Records followed in the spring. Barry was also a sideman on the date, and he pitched another money-making idea to Michael. Goldberg had a manager friend who wanted to assemble yet another super group. The manager had bassist Rick Grech, formerly of Blind Faith, and drummer Carmine Appice, formerly of the Vanilla Fudge, interested in the project, and he was eager to shop the concept around to record companies. "We'll clean up!" was the manager's selling point to Michael.

By the early summer, a deal had been worked out with MCA for the group – curiously named KGB, after the Russian secret police – to record an album. MCA's interest, as far as Michael was concerned, was solely in the "bankability" of the band; the music was irrelevant to the label's corporate managers. To them KGB was a product, like soap or breakfast cereal.

Bloomfield and the other members of KGB got along well and actually liked each other, but the artifice behind their collaboration was too thin to withstand all the pressures from the front office. After studio sessions in Los Angeles in June, and overdubbing dates later in Sausalito, Michael was thoroughly disgusted with the superficiality of the whole business.

He was enough disgruntled that, following the release of the band's eponymous album in February 1976, he gave a tell-all interview to the Los Angeles Times in which he took the band and record company to task. Michael opined that KGB had everything to do with business and nothing to do with art. He followed that impolitic move with a two-page letter to MCA that was part harangue, part resignation. Everyone involved was furious with him, and by April KGB was effectively dead in the water.

KGB before the break-up: from left, Carmine Appice, Ric Grech, Barry Goldberg, Michael Bloomfield and Ray Kennedy. MCA promotional photoThe whole affair left Michael with an overwhelming desire to do something with integrity.

KGB before the break-up: from left, Carmine Appice, Ric Grech, Barry Goldberg, Michael Bloomfield and Ray Kennedy. MCA promotional photoThe whole affair left Michael with an overwhelming desire to do something with integrity.

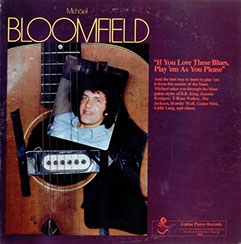

Guitar Player magazine, a glossy music publication that had appeared in 1967, had recently launched a music division. Michael was a member of their advisory board, and they had done a number of extensive interviews with him as a favored son. It seemed only natural that he should be one of the first artists to record for the magazine's new label. Bloomfield decided he would create an omnibus of the blues, a tribute to the many performers and styles that he had come to know and love.

In the summer of 1976, Michael worked on the recording with his friend Norman Dayron at Blossom Studios in San Francisco. Using players from his working band and other friends and neighbors, he created a series of vignettes based on the disparate styles of country, urban, acoustic and electric blues giants. Exhibiting an extraordinary ear for each artist's distinctive sound, Michael recorded tunes that evoked by turns B.B. King, Guitar Slim, Lonnie Johnson, Jimmie Rodgers, John Lee Hooker and Jim Jackson. To further engage the listener, he added brief introductory statements before each selection in which he gave a bit of history, the key and the technique and equipment used. A final tune, aptly titled "The Altar Song," consisted of a recitation of the names of all the blues artists to whom Michael felt indebted over a lush gospel melody.

The resulting album – "If You Love These Blues, Play 'Em as You Please" – was unlike anything else by a contemporary artist. Billed by Guitar Player as an  instructional record, the album was really more of a guide to blues styles and players. Michael was completely satisfied with it, and felt he had made amends for the musical indiscretions of years previous. When the album was released in December 1976, it was immediately nominated for a Grammy Award in the Best Traditional Recording category. It didn't win, but the recognition was a clear indication that the industry felt that Michael Bloomfield had finally produced something worthy of his legacy.

instructional record, the album was really more of a guide to blues styles and players. Michael was completely satisfied with it, and felt he had made amends for the musical indiscretions of years previous. When the album was released in December 1976, it was immediately nominated for a Grammy Award in the Best Traditional Recording category. It didn't win, but the recognition was a clear indication that the industry felt that Michael Bloomfield had finally produced something worthy of his legacy.

Ironically, the record went out of print within a few months of its release when Guitar Player's label failed to prove profitable and closed down.

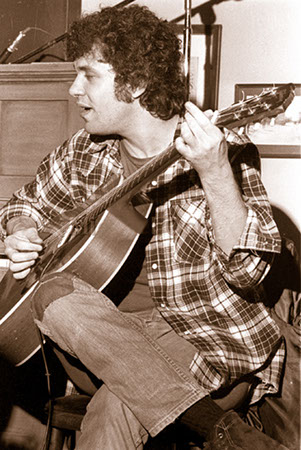

Meanwhile, Michael had discovered a new favorite place to play. Located on Divisadero St. in San Francisco, it was a small, hole-in-the-wall bar called the Old Waldorf. The owner had agreed to let the guitarist and his friends perform there on weekends for whatever they could charge at the door. The seedy nature of the place and the casualness of the  Bloomfield plays an acoustic opening set at the Old Waldorf in 1976. Tom Copi photoarrangement reminded Michael of his Chicago days, and for the first time in quite a while he felt truly comfortable performing. He was there nearly every weekend when he was in town, and Norman Dayron, ever ready with a tape recorder, often taped the proceedings.

Bloomfield plays an acoustic opening set at the Old Waldorf in 1976. Tom Copi photoarrangement reminded Michael of his Chicago days, and for the first time in quite a while he felt truly comfortable performing. He was there nearly every weekend when he was in town, and Norman Dayron, ever ready with a tape recorder, often taped the proceedings.

In June, Bloomfield took a quartet to New York City for an appearance at the 1976 Newport Jazz Festival. Billed as a "midnight blues concert," the show also featured Bobby "Blue" Bland, Fats Domino and Muddy Waters. Bloomfield played traditional tunes on acoustic guitar and then plugged in for some electric blues with the rest of the band, echoing the approach he'd taken with "If You Love These Blues ..." Though a New York Times review of the show wasn't very favorable, the audience was wildly appreciative and clearly relished the rare opportunity to see one of the idiom's great players.

While in New York, Michael picked up another soundtrack job. Jed Johnson, a film director for Andy Warhol, was working on a film that starred Carroll Baker called "Andy Warhol's Bad." Bloomfield connected with Warhol and Johnson through fashion  designer and friend Tere Tereba. She had a supporting role in the film and had convinced them that Michael was the right man for the soundtrack job. When he returned to California, he told Norman Dayron to expect a shipment of raw footage from the Pop artist. Several days later, seventeen canisters of 35-mm film arrived on Norman's doorstep. Having no way to look at the rushes, he and Michael simply created the music from the film's screenplay, much as they had done with their Mitchell Brothers projects.

designer and friend Tere Tereba. She had a supporting role in the film and had convinced them that Michael was the right man for the soundtrack job. When he returned to California, he told Norman Dayron to expect a shipment of raw footage from the Pop artist. Several days later, seventeen canisters of 35-mm film arrived on Norman's doorstep. Having no way to look at the rushes, he and Michael simply created the music from the film's screenplay, much as they had done with their Mitchell Brothers projects.

In January 1977, Bloomfield did a number of concerts at McCabe's Guitar Shop in Santa Monica and featured his acoustic playing. His repertoire now included scores of classic and obscure blues tunes, numerous gospel and spiritual songs, and more than a few originals. He played them on piano as well as guitar, and then brought on the band to finish the set with several rousing electric numbers.

Local fans knew Michael's acoustic and folkloric inclinations very well. But when he played out of town, folks who came to his concerts were more often than not expecting the music they knew from the Butterfield or "Super Session" albums. Catcalls for "Season of the Witch" became common at performances when Bloomfield was on the road, and the guitarist, at first bemused, became more and more annoyed at the requests as the '70s wore on.

BLOOMFIELD BIOGRAPHY continued

CONTACT | ©2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD | AN AMERICAN GUITARIST