RICH KID

The son of a wealthy restaurant supply manufacturer, Michael Bloomfield was meant to go into the family business. But it was the music of his Chicago neighborhood that caught his attention. Given a guitar at age 13, he became the country's first great blues-rock master.

BIOGRAPHY

Michael Bloomfield with his paternal grandmother, Ida, at his bar mitzvah in 1956. Photo courtesy of Allen Bloomfield

GUITAR SUPERSTAR

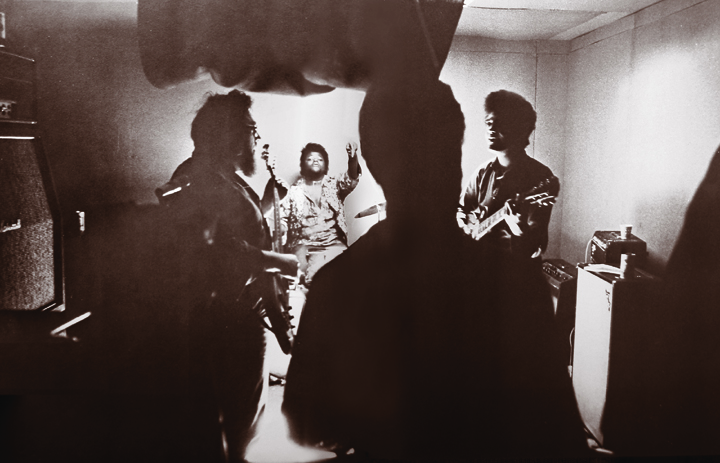

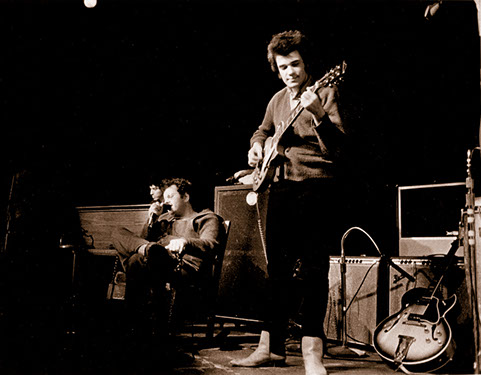

The Electric Flag rehearses at the Heliport in Sausalito in the fall of 1967. From left, Harvey Brooks, Buddy Miles, Herbie Rich and Michael Bloomfield. Photo by Bob Cato

IT WAS WITH COLUMBIA'S Clive Davis that Albert Grossman successfully negotiated a deal following the Flag's Monterey appearance. The band would record for the label that had successfully marketed Grossman's star client, Bob Dylan. Michael and the group were surprised by the choice – they thought their music was better suited for Jerry Wexler and the Atlantic label. After all, much of the music they admired have been released on Atlantic. But Grossman was able to get more money from Columbia, and that sealed the deal.

The Heliport in Sausalito. Photo by Kim RushThe Flag rented rehearsal space at Sausalito's Heliport, an old helicopter hanger used by local bands as a place to practice, and began working up material. In September, the band was booked for several weeks into the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, the venue Michael had played numerous times as a member of the Butterfield Blues Band. On the evening of September 30, police officers responding to a noise complaint arrested Barry Goldberg, Harvey Brooks, Nick Gravenites and Bloomfield in Goldberg's room at the Huntington Beach Motel. The four had been caught with marijuana, a "narcotics violation." They were arraigned at the police station and given a court date of October 20.

The Heliport in Sausalito. Photo by Kim RushThe Flag rented rehearsal space at Sausalito's Heliport, an old helicopter hanger used by local bands as a place to practice, and began working up material. In September, the band was booked for several weeks into the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach, the venue Michael had played numerous times as a member of the Butterfield Blues Band. On the evening of September 30, police officers responding to a noise complaint arrested Barry Goldberg, Harvey Brooks, Nick Gravenites and Bloomfield in Goldberg's room at the Huntington Beach Motel. The four had been caught with marijuana, a "narcotics violation." They were arraigned at the police station and given a court date of October 20.

While no small matter, the Flag's Huntington Beach bust was only a symptom of a much larger problem – that of hard drug use among certain members of the band. While grass and LSD were commonly used by most of the members, Marcus Doubleday had been a habitual heroin user before joining the band and Peter Strazza was soon addicted. Barry had started using the drug before leaving New York, and Michael, who at first was unaware of the horn players' narcotics use, was soon experimenting with heroin, too. A roadie with the band acted as procurer, and in short order the Flag was often flying on more than just its musical prowess.

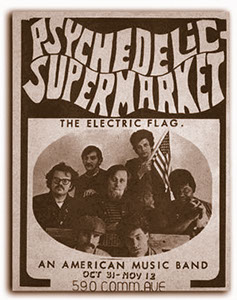

The court appearance delayed the band's first real road trip until the third week in October. Beginning  October 23, the Flag spent a month on the road, traveling to Wisconsin and Massachusetts before appearing in New York City for their official East Coast debut. To get their sets together, they did several weeks at a converted parking garage in Boston called the Psychedelic Supermarket. Reviews were good, even though the Flag had only its single, "Groovin' Is Easy," for support. The band featured a mix of soul covers, blues and a handful of originals, all leavened with Michael's protean solos and Buddy Miles' overwrought vocals.

October 23, the Flag spent a month on the road, traveling to Wisconsin and Massachusetts before appearing in New York City for their official East Coast debut. To get their sets together, they did several weeks at a converted parking garage in Boston called the Psychedelic Supermarket. Reviews were good, even though the Flag had only its single, "Groovin' Is Easy," for support. The band featured a mix of soul covers, blues and a handful of originals, all leavened with Michael's protean solos and Buddy Miles' overwrought vocals.

The shows were tight, impressive and hugely entertaining. But they were also considerably more conventional than the band's earlier work for "The Trip." The experimentation that marked Bloomfield's material for Roger Corman seemed to have gotten lost in the need to rapidly assemble a book of tunes for the Flag's many performance dates. Bloomfield's vision of music drawn from across the spectrum of American styles seemed to have been abandoned in favor of a jumble of standard blues and R&B numbers.

There were exceptions. "Another Country," by Nick Gravenites, featured a startling free-form section, a sound collage that morphed into a jazzy guitar-and-rhythm solo from Michael. And there were occasional extended jams that evoked the "East-West" days and allowed Bloomfield to explore the outer reaches of his formidable talent.

In New York City, the band played two weeks at the Bitter End. The New York Times touted their arrival, but the Flag's appearance was complicated by the loss of one of its founding members.

Buddy Miles works the crowd as Bloomfield accompanies him during the Electric Flag's New York debut at the Bitter End in November 1967. Don Paulsen photo for Hit ParaderBarry Goldberg, fearful of becoming a full-blown junkie and increasingly reluctant to travel, decided to leave the band soon after the Boston gig ended. He was quickly replaced by a fine player from Canada, a friend of Buddy Miles' named Michael Fonfara. The band's sound was not significantly affected, but the departure of Bloomfield's long-time friend further shifted the balance of control toward Buddy Miles and also underscored the real threat that drugs posed.

Buddy Miles works the crowd as Bloomfield accompanies him during the Electric Flag's New York debut at the Bitter End in November 1967. Don Paulsen photo for Hit ParaderBarry Goldberg, fearful of becoming a full-blown junkie and increasingly reluctant to travel, decided to leave the band soon after the Boston gig ended. He was quickly replaced by a fine player from Canada, a friend of Buddy Miles' named Michael Fonfara. The band's sound was not significantly affected, but the departure of Bloomfield's long-time friend further shifted the balance of control toward Buddy Miles and also underscored the real threat that drugs posed.

Despite the changes, though, the Flag had a triumphant homecoming weekend at the Fillmore and Winterland for Bill Graham. Though the Byrds were headlining, B.B. King was also on the bill and Michael – having arranged for the Flag to go on first – took great pleasure in introducing his idol to the uninitiated in the audience.

BUT THINGS WERE not well in the Bloomfield household. Susan, Michael's wife of five years, announced in December that she had decided to leave him. With Michael preoccupied with the welfare of his band, out at gigs or on the road much of the time and at home primarily to catch up on his sleep, she felt they had grown apart. She and Michael separated in early 1967.

There were more personnel changes in the band, too. Mike Fonfara had been arrested for drug possession in Los Angeles in mid-December and – because he was not an American citizen – had been dropped from the band on Grossman's orders. Baritone player Herbie Rich, a talented multi-instrumentalist, took over keyboard duties. Buddy added another friend form Omaha to fill out the horn section, a saxophonist named Stemzie Hunter

Gigs at the Fillmore, the Avalon and other California venues filled out the months of January and February. At the end of February, Rolling Stone magazine editor  Jann WennerJann Wenner did an extensive interview with Michael. The two discussed Michael's early days in Chicago, his stints with Dylan and Butterfield, and his thoughts about the Electric Flag. Wenner also got Bloomfield to speak on a range of other topics, including the role of race in music, the San Francisco scene and the blues. The interview was scheduled to appear in April, right around the time Columbia hoped to have the Flag's first record in store bins.

Jann WennerJann Wenner did an extensive interview with Michael. The two discussed Michael's early days in Chicago, his stints with Dylan and Butterfield, and his thoughts about the Electric Flag. Wenner also got Bloomfield to speak on a range of other topics, including the role of race in music, the San Francisco scene and the blues. The interview was scheduled to appear in April, right around the time Columbia hoped to have the Flag's first record in store bins.

The band was soon back on the road, heading to New York City for a show at the Anderson Theater and a two-week stand at the Cafe Au Go Go. Then, on March 19, the Flag again ran afoul of its bad habits. While enroute to the West Coast, they played a show in Detroit and were robbed in their motel rooms. The event was reported as a brazen hold-up, but it was almost certainly a drug deal gone bad. A member of the band had been short of cash while making a buy, and the enraged dealers took him at gun point into the other members' rooms in search of their money. They made off with whatever they could find, and Grossman had to wire the band additional funds to complete the trip home.

By the spring of 1968, drug use in the Flag had become a serious problem. In addition to putting the band at risk, it was also affecting the Electric Flag's ability to perform. There were other complications for Michael, too. Buddy Miles, a force to be reckoned with from the start, had effectively taken over the band by April 1968. His stage routine was built around the Chitlin' Circuit antics he had learned with Wilson Pickett and other soul shouters, and he loved nothing more than to whip the audience into a frenzy with vocal feints and histrionics, false endings, "clap-your-hands" interludes and impromptu call-and-response moments. He would leave the drums in mid-performance and cavort around the stage, mic in hand, improvising lyrics and generally taking over. While audiences were usually thrilled by Buddy's showboating, Michael hated it. "I'm no entertainer," he later said. His experience at Monterey was no doubt still fresh in his mind.

"A Long Time Comin'," the Electric Flag's long-awaited debut release, finally reached record store bins the first week in April. The hype surrounding the band at Monterey had long since dissipated, and while the record was quite good by  contemporary standards, it received mixed reviews and had little impact on the pop music world. It rose briefly to number 31 on Billboard's charts, a fair showing, but well short of the success originally expected for Michael Bloomfield's American music band.

contemporary standards, it received mixed reviews and had little impact on the pop music world. It rose briefly to number 31 on Billboard's charts, a fair showing, but well short of the success originally expected for Michael Bloomfield's American music band.

Concurrently, Rolling Stone's interview with Mike Bloomfield appeared in the April 6 issue. Bloomfield's ideas on music, race, blues, rock 'n' roll and his own place in their evolution were spread across five full pages, with the promise of a second installment in the magazine's subsequent issue. Michael came off as a highly animated, a larger-than-life savant whose opinions were hard-edged and legion. His respect for his antecedents and his disdain for musical wannabes – especially those found in San Francisco – was offered with unqualified and assured candor. It was the world according to Michael Bloomfield.

Oddly, there were no plans for the Electric Flag to tour in support of their Columbia release. They continued to play venues in San Francisco and Los Angeles, but there were no preparations for a third cross-country junket to promote "A Long Time Comin'." Bloomfield, who by May 1968 was thoroughly disillusioned with the group, may have told Grossman that he wouldn't go along on another road trip. In fact, he told Albert that he intended to quit the band he had formed nearly one year ago.

ON MAY 11, BLOOMFIELD was caught off guard by a column in Rolling Stone. San Francisco jazz critic and icon, Ralph Gleason, lambasted Michael for things he said in his interview and for his failure – in Gleason's opinion – to find his own voice with the Flag. Headlined "Stop this shuck, Mike Bloomfield," the caustic column punctured Michael's  Ralph Gleasonapparent inflated sense of himself and came off as an ad homonym bromide that questioned the guitarist's ability to play blues based on his racial background. Gleason's main criticism, though, was a valid one, and must have hit home. He chided Bloomfield for not fulfilling his potential as "one of the best guitar players in the world."

Ralph Gleasonapparent inflated sense of himself and came off as an ad homonym bromide that questioned the guitarist's ability to play blues based on his racial background. Gleason's main criticism, though, was a valid one, and must have hit home. He chided Bloomfield for not fulfilling his potential as "one of the best guitar players in the world."

The discomfort of Monterey's failure had been captured in a single sentence.

Michael's friend and fellow bandmate, Nick Gravenites, wrote a bristling response to Gleason in the next edition of Rolling Stone. He vigorously defended Bloomfield's right to play a music he had grown up with, but the damage was done. Michael was thoroughly disheartened by Gleason's accusations, and he was more determined than ever to remove himself from the spotlight.

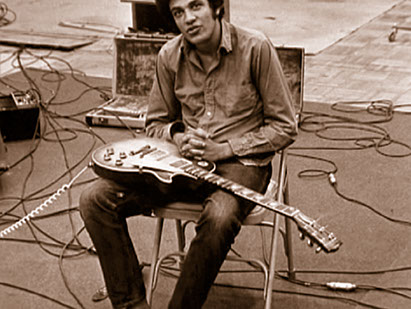

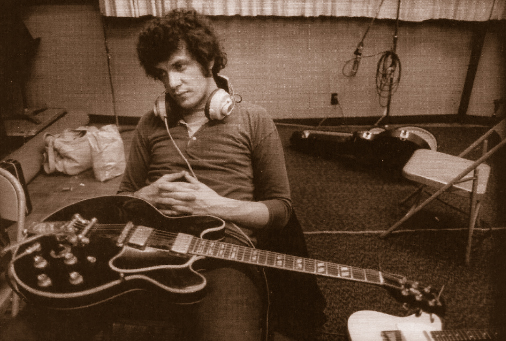

But while Bloomfield was trying to extricate himself from the Electric Flag, he got a call from Al Kooper. Kooper, who had recently quit his own horn band Blood, Sweat & Tears, was working as an A&R man for Columbia. He needed a project, and he proposed to Michael that they go into the studio, jam on a few tunes and see what would happen. It  Bloomfield takes a break during Al Kooper's May 28, 1968 jam session date in Los Angeles, a taping that resulted in "Super Session." Jim Marshall photowould be a session not unlike what jazz artists had been doing for decades. Michael reluctantly agreed to the plan and met Kooper in a Los Angeles studio on the evening of May 28. They were joined by Eddie Hoh, the drummer from The Mamas & the Papas, and the Flag's bass player, Harvey Brooks. Barry Goldberg sat in on piano. Over the course of six hours, they recorded five impressive tunes and then retired for the night.

Bloomfield takes a break during Al Kooper's May 28, 1968 jam session date in Los Angeles, a taping that resulted in "Super Session." Jim Marshall photowould be a session not unlike what jazz artists had been doing for decades. Michael reluctantly agreed to the plan and met Kooper in a Los Angeles studio on the evening of May 28. They were joined by Eddie Hoh, the drummer from The Mamas & the Papas, and the Flag's bass player, Harvey Brooks. Barry Goldberg sat in on piano. Over the course of six hours, they recorded five impressive tunes and then retired for the night.

In the morning, Bloomfield was nowhere to be seen. He later told Kooper that he couldn't sleep and had decided to go home to Mill Valley. Kooper suspected that his departure was drug related. In any event, Al enlisted Steve Stills to complete the session.

Michael made arrangements to reimburse Albert Grossman for advances and other expenses related to the Electric Flag and was officially through with the band by June following an appearance with the Flag at Graham's newly-opened Fillmore East. The Electric Flag played its last shows with Michael Bloomfield on June 7 and 8 in New York City. The New York Times called their final appearance a "sentimental moment and a crossroads event."

And then the original Electric Flag was no more.

Mike Bloomfield retired to his home on Wellesley Court in Mill Valley, just as he had done after leaving the Butterfield Band. But this time he was not energized, ready to strike out on his own. He visited his family in Chicago,  recorded as a sideman for Barry Goldberg and for a new group produced by Mark Naftalin called Mother Earth, and tried to sort things out.

recorded as a sideman for Barry Goldberg and for a new group produced by Mark Naftalin called Mother Earth, and tried to sort things out.

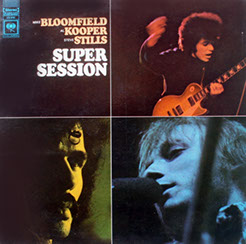

The album that he had recorded with Al Kooper in May was released in August. Called "Super Session," Bloomfield was featured on one side and Steve Stills on the other. It was a surprise hit, reaching number 12 on Billboard's charts. Critics agreed that Bloomfield's playing was masterful, and Kooper prided himself on having captured for the first time in the studio the guitarist's distinctive sound. Michael, who initially thought he had played well, was appalled by the superficiality of the result. He felt that the elevation of a casual jam to "super" status was nothing more than music business cynicism. Privately, though, he could not have missed the irony in the fact that "A Long Time Comin'," an album he had spent months laboring to create while battling with Columbia's conservative engineers and attempting to expand upon the innovations of producers like Bob Crewe and Phil Spector, had received a tepid response upon release, while an impromptu jam session that nearly hadn't happened was receiving accolades.

But Al Kooper – no slouch as a businessman – saw an opportunity. He arranged to do a live version of "Super Session," one that would be recorded by Columbia at Bill Graham's Fillmore Auditorium. He talked Bloomfield into joining him.

When the Super Session quartet took the stage at the Fillmore on September 26, Bloomfield was in a state of nervous exhaustion. Four days of rehearsals and the anticipation of another gig that would largely be carried by his ability as a soloist had deprived him of sleep and had pushed his normally hyperactive nature into overdrive. After two nights of performances, he collapsed and had to be hospitalized. Kooper was once again left to find last minute  Al Kooperreplacements and this time he called on the services of Elvin Bishop, Carlos Santana and Steve Miller. The result was eventually released in February 1969 as "The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper," a two-record set on Columbia.

Al Kooperreplacements and this time he called on the services of Elvin Bishop, Carlos Santana and Steve Miller. The result was eventually released in February 1969 as "The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper," a two-record set on Columbia.

Sales, while not as brisk as for "Super Session," were still good. Mike Bloomfield thought the playing had more validity than it had on the earlier session, but he was still critical of the concept. Kooper went ahead and arranged additional live appearances in support of the records, trusting that Michael would be able to make it through the gigs. And Bloomfield, for all his protestations about the value of jams, began making plans for his own mammoth jam session at the Carousel Ballroom, now known as the Fillmore West.

In mid-December, at Albert Grossman's request, Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites helped Janis Joplin organize a new band. Grossman, Joplin's manager, had decided the singer should leave Big Brother and the Holding Company and form her own group. Mike and Nick rehearsed the musicians at the Fillmore and, while assisting them in getting their sound together, taped a few sessions with Janis. Joplin christened the new group the Kozmic Blues Band.

AFTER THE NEW YEAR, Bloomfield was busy rehearsing his own band. This one would perform live over two long weekends at the new Fillmore West, and the dates would be billed as "The Jam." Michael was still under contract to Columbia, and the label, seeing the success of "Super Session" and "Live Adventures," made arrangements to record the proceedings on the off chance that the performances might be marketable. Bloomfield, in turn, saw the gig as an opportunity to easily fulfill his contract commitment to Columbia for another record.

Michael gathered together an informal group of friends, using players from the now defunct Electric Flag and from the Butterfield Band as well as musicians he knew from the Bay Area. The resulting group very much resembled an expanded version of the Flag, with the conspicuous absence of Buddy Miles. Material included tunes Michael had done with his former band as well as blues and soul covers and a number of originals by Nick Gravenites and Bloomfield himself. Calling the aggregation Mike Bloomfield & Friends, he invited other San Francisco musicians to come by and sit in, giving the whole performance a comfortable, relaxed feeling.

"The Jam," a live jam session Bloomfield organized to fulfill his contract with Columbia, was recorded and released as "Live at Bill Graham's Fillmore West" in 1969. Here Michael accompanies Nick Gravenites as Ira Kamin plays organ. Jim Marshall photo Columbia recorded each night and eventually issued an album the following October titled "Live at Bill Graham's Fillmore West." The label also used some of the material for a portion of Nick Gravenites' solo record, "My Labors." Though both contained exciting performances, the records didn't find an audience and were quickly deleted from the catalog.

Columbia recorded each night and eventually issued an album the following October titled "Live at Bill Graham's Fillmore West." The label also used some of the material for a portion of Nick Gravenites' solo record, "My Labors." Though both contained exciting performances, the records didn't find an audience and were quickly deleted from the catalog.

Bloomfield, however, had found a working situation that he was comfortable with. He had surrounded himself with friends who were available whenever he needed them and he had played a venue that was close to home. He saw that he didn't need an organized group with its concurrent personality issues and management problems, and he didn't need to travel. It would become his preferred method for presenting his music throughout the '70s.

In April, Mike flew to Chicago to go into the studio with his old friend and mentor, Muddy Waters. He had earlier proposed a meeting of blues masters with their younger followers to Marshall Chess, son of Chess Records founder Leonard Chess, and Marshall, eager to prove himself as a producer, had acted on the idea. He and Michael's old friend, Norman Dayron, organized a recording date that would include Muddy and Otis Spann and their former protégés, Paul Butterfield and Michael Bloomfield. Added for good measure were bass player Donald "Duck" Dunn from Booker T & the MGs, former Butterfield drummer Sam Lay, and Michael's ex-bandmate, powerhouse Buddy Miles.

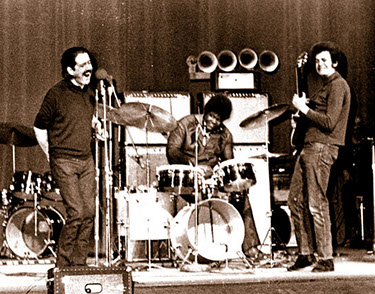

Paul Butterfield, Buddy Miles and Michael Bloomfield perform on stage at Chicago's Civic Auditorium in April 1969, during a "Fathers and Sons" tribute to legendary bluesman Muddy Waters. Photographer unknown Marshall Chess had additional plans for the group he'd assembled, and he arranged for a tribute concert for Muddy to follow the recording sessions. On April 24, Muddy Waters and the musicians from the "Fathers & Sons" sessions – the name Michael had given the project – did two sets at the Civic Auditorium in downtown Chicago for a capacity crowd. Bloomfield, looking drawn and intense, turned in an excellent performance, sharing the stage at first with his former boss, Paul Butterfield, and then backing up blues legend Muddy Waters. Rolling Stone reviewed the show and had high praise for the blues portion of the evening.

Marshall Chess had additional plans for the group he'd assembled, and he arranged for a tribute concert for Muddy to follow the recording sessions. On April 24, Muddy Waters and the musicians from the "Fathers & Sons" sessions – the name Michael had given the project – did two sets at the Civic Auditorium in downtown Chicago for a capacity crowd. Bloomfield, looking drawn and intense, turned in an excellent performance, sharing the stage at first with his former boss, Paul Butterfield, and then backing up blues legend Muddy Waters. Rolling Stone reviewed the show and had high praise for the blues portion of the evening.

Michael headed back to San Francisco immediately after the Chicago blues summit and went to work in the studio. His contract with Columbia stipulated that he complete a solo album and he was determined to fulfill that obligation. But Bloomfield didn't want to make another jam session record. He decided he would use the album to make a personal statement.

Michael created a number of original songs for the recording, and decided he would sing them all himself. He was by no means a natural singer, but he was determined to get his point across and saw no better way to do that than to feature himself as vocalist.

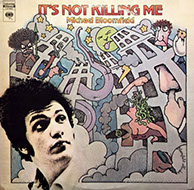

Of the new material for the sessions, four tunes stood out as intensely personal – and intensely disturbing – reflections of Bloomfield's mental and emotional state. "Far Too Many Nights" described Michael's anxiety and insomnia, while "Michael's Lament," a gospel-style dirge told of his loneliness. "It's Not Killing Me" characterized the chaotic state of his life, opining that "I sit and twitch, Lord, I itch and bitch over some small mental mistake ... I'm starting to rot." But it was  "The Ones I Loved Are Gone," a hymn-like anthem about the break-up of Bloomfield's marriage, that expressed the deep pain Michael was feeling in his life. His quirky vocal seemed at times more a wail, bemoaning the "sad things on my mind."

"The Ones I Loved Are Gone," a hymn-like anthem about the break-up of Bloomfield's marriage, that expressed the deep pain Michael was feeling in his life. His quirky vocal seemed at times more a wail, bemoaning the "sad things on my mind."

Bloomfield worked on the recording through the summer months. Feeling insecure about his vocals, he repeatedly redid them and his guitar solos at Wally Heider's studios in San Francisco. While his guitar playing was as good as ever, the retakes did little to improve his singing. The LP, titled "It's Not Killing Me," came out in early October 1969.

Reviewers hated it. Lacking any real understanding of what Bloomfield was going through at the time, and expecting more "Super Session" pyrotechnics, they were greatly disappointed that Michael's first solo release seemed to be no more than a hash of faux country tunes and unremarkable blues performances. And for some inexplicable reason, Bloomfield not only thought he could sing but had decided to showcase himself as a vocalist rather than as the topnotch guitarist that people knew him to be. The album went nowhere.

NO ENTERTAINER

Bloomfield relaxes with a book and his dog Harry on the porch of his Wellesley Court home in Mill Valley in 1968. He had recently quit the Electric Flag and was recuperating from three years of constant touring. Alice Ochs photo

MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD WENT nowhere, too. Once his solo album had been completed, he stayed home, read books, watched TV and indulged in heroin whenever his depression got too great. Occasionally he did studio sessions, recording with Barry Goldberg, with the folk duo Brewer & Shipley and with Wayne Talbert, a pianist whom he'd met through his friends in Mother Earth. His father's cousin, Haskell Wexler, a filmmaker, asked him to provide the soundtrack for a feature-length movie he was completing called "Medium Cool."

In June Michael spent a week in New York City, doing sessions with Janis Joplin for "I Got Them Ol' Kozmic Blues Again, Mama!" But he and Janis spent much of their time together on the streets searching for a drug connection. There were also a few gigs in local bars and clubs, but Bloomfield seemed to have lost his way. A Rolling Stone article quoted him as saying of his future in music, "I just don't know ..."

Michael's friends in the San Francisco music community were alarmed at his determined dissipation. Terry Haggerty and Carlos Santana, guitarists who had idolized Bloomfield when they were just starting out, paid Michael separate visits and chided him for letting his talents languish. Though he was moved by their entreaties, Michael could only agree with them that he was wasting his gifts.

At the same time, Mike and Nick Gravenites had come across a North Beach tavern that was struggling to make ends meet. Called Keystone Korner, the place was a perfect venue for the sort of ad hoc, loosely organized performances that Bloomfield favored. He and Nick approached the owner and convinced him to allow them to produce weekly shows, much as Michael had done at the Fickle Pickle back in Chicago. In short order, Elvin Bishop, Charlie Musselwhite and other artists were performing on alternating weekends with Bloomfield and Gravenites. The shows brought in the crowds, and in no time Keystone Korner was one of the Bay Area's hot clubs.

But Michael was still reluctant to commit to anything more than local gigs and the occasional studio session. His playing had improved, and his health was better, but it was his home life that now gave him the most satisfaction. As far as the general public was concerned, however, Michael Bloomfield had disappeared from view.

THERE WERE MORE studio sessions for Michael Bloomfield throughout the spring and summer of 1971. Then, on July 4, Bill Graham's Fillmore West ended its three–year existence with a gala closing night jam. Bloomfield led one of the  Christie Svaneevening's final sessions with guitarists Carlos Santana and John Cipollina, jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi, Santana's rhythm section and the horns from Tower of Power. At the post–closing party, Michael rekindled a relationship with Christina Svane, a young woman he'd first met some years earlier. Svane would become Bloomfield's on–again, off–again companion for the remainder of his life.

Christie Svaneevening's final sessions with guitarists Carlos Santana and John Cipollina, jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi, Santana's rhythm section and the horns from Tower of Power. At the post–closing party, Michael rekindled a relationship with Christina Svane, a young woman he'd first met some years earlier. Svane would become Bloomfield's on–again, off–again companion for the remainder of his life.

Though Michael had broken his habitual use of narcotics, he still was a sometime user of heroin, and there could be periods of prolonged inactivity. Bloomfield's disinclination to work was further exacerbated by a trust fund that his paternal grandmother had created for him, a nest egg that paid out $50,000 on an annual basis. If he were careful with the money, Michael could have had a comfortable living without needing to earn another dime. But his his generosity and absolute disregard for material things invariably ran up bills that needed to be paid. That was when Michael would assemble a band and arrange for a few months of performances.

Despite his lethargy, Bloomfield's playing remained as good as it had ever been. The irony was that aside from an occasional appearance as a sideman on someone else's record, Michael was silent – most Bloomfield fans heard nothing at all from him. Unless they were fortunate enough to be in the audience at one of his San Francisco gigs or chanced to catch him at an infrequent appearance in Los Angeles or New York, their only reference point was "Super Session" or the early Butterfield records.

A partial reunion of the Butterfield Band took place at the Fenway Theater in Boston in 1971 with Bloomfield, leader Paul Butterfield and keyboardist Mark Naftalin. Dave Agerholm photoIn an effort to capitalize on those heady days, Paul Butterfield's manager Albert Grossman arranged a reformation of the "original Paul Butterfield Blues Band" for a two-night concert in Boston during Christmas week. It didn't really matter that three of the six original members didn't participate – everyone wanted to hear what Butterfield and Bloomfield would sound like together again. With Billy Mundi and John Kahn substituting for Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold, the band took the stage as a quintet on December 21 and 22, and proved that the fire was still there. But there were no plans for anything beyond the two nights. Bloomfield returned to Mill Valley and Butterfield went back on the road with his current band.

A partial reunion of the Butterfield Band took place at the Fenway Theater in Boston in 1971 with Bloomfield, leader Paul Butterfield and keyboardist Mark Naftalin. Dave Agerholm photoIn an effort to capitalize on those heady days, Paul Butterfield's manager Albert Grossman arranged a reformation of the "original Paul Butterfield Blues Band" for a two-night concert in Boston during Christmas week. It didn't really matter that three of the six original members didn't participate – everyone wanted to hear what Butterfield and Bloomfield would sound like together again. With Billy Mundi and John Kahn substituting for Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold, the band took the stage as a quintet on December 21 and 22, and proved that the fire was still there. But there were no plans for anything beyond the two nights. Bloomfield returned to Mill Valley and Butterfield went back on the road with his current band.

Throughout 1972, Michael Bloomfield continued to play locally and do studio work. In the fall, he and Nick Gravenites began work on another soundtrack, this time for director Alan Myerson and Warner Brothers. The film Myerson was making was called "Steelyard Blues" and it concerned a group of misfits who were looking for a way to escape the strictures of conventional society – not unlike Michael and his friends. Bloomfield and Gravenites wrote all the material and hired Paul Butterfield and Maria Muldaur to perform it with them at Golden State Recorders in San Francisco. The resulting album was released in February 1973 and received better reviews than did the film. But Michael's playing remained in the background on most of the soundtrack's tunes, and for fans it was not really a Bloomfield record.

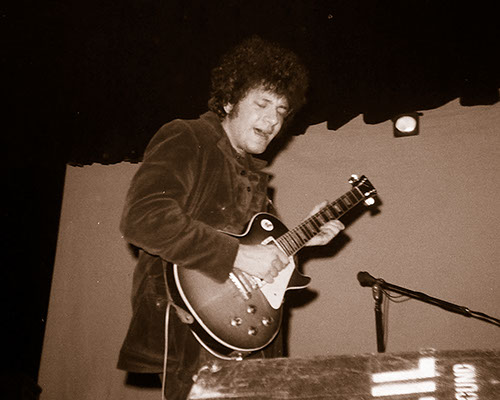

1973 BEGAN WITH Michael Bloomfield getting involved with one of several ill-fated projects. For the first time in four years, he agreed to participate as a leader on a recording session. His longtime friend, guitarist and singer John Hammond, asked him to collaborate on an album of blues and New Orleans R&B. Hammond had also gotten Dr. John to sign on, and had scheduled studio sessions for January. Michael agreed to participate, even though he was leery of  Michael Bloomfield in early 1973, during a break while recording with John Hammond and Dr. John for Hammond's release, "Triumvirate." Jim Marshall photogetting involved in another “super group.”

Michael Bloomfield in early 1973, during a break while recording with John Hammond and Dr. John for Hammond's release, "Triumvirate." Jim Marshall photogetting involved in another “super group.”

The sessions didn't go smoothly, however, and Hammond eventually had to replace some of the sidemen. When Columbia issued the album, called "Triumvirate," in June 1973, the company's president, Clive Davis, was being investigated by the FBI for embezzling funds. All of Columbia's projects were put on hold, and the tour Hammond had arranged for the trio was canceled. As a result, the record received tepid reviews and failed to sell. For Michael, it was another unpleasant instance of hype and its ensuing expectations – a circumstance he was now more determined than ever not to repeat.

But 1973 was also the year that Michael Bloomfield finally began to perform in public with more regularity. There were several extensive tours that took his Friends quartet to places as distant as Miami, Boulder, Chicago, Bangor, Boston, Toronto, Buffalo and Woodland, Alabama. Michael's working band now included his close friend and musical partner Mark Naftalin, bassist  Bob DylanRoger Troy and drummer George Rains. Nicknamed "Jellyroll," Troy was also a talented singer and added a new versatility to the Friends. Rains, a native of Fort Worth, had been a member of Mother Earth. The group worked together frequently enough that they developed a tight, cohesive sound, often inspiring Michael to new heights as a soloist.

Bob DylanRoger Troy and drummer George Rains. Nicknamed "Jellyroll," Troy was also a talented singer and added a new versatility to the Friends. Rains, a native of Fort Worth, had been a member of Mother Earth. The group worked together frequently enough that they developed a tight, cohesive sound, often inspiring Michael to new heights as a soloist.

In August, Bloomfield had an unexpected visitor. His old friend, Bob Dylan, dropped by for what amounted to an audition. Over the course of several hours, Dylan ran through a series of new tunes while Michael tried to play along. Bob was soon to go into the studio to record "Blood on the Tracks," and he felt that the quality of the songs merited the playing of his old "Highway 61 Revisited" collaborator. But Michael was thrown by Dylan's D–tuning and odd fingerings, and he had trouble following the singer's changes. The superstar later decided against using Michael on what would be an historic session.

BLOOMFIELD BIOGRAPHY continued

MICHAEL BLOOMFIELD | AN AMERICAN GUITARIST

CONTACT | ©2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED